Bad Breath (Halitosis)

October 23, 2017Cholangitis

October 23, 2017Correlation of the stomach and oesophagus

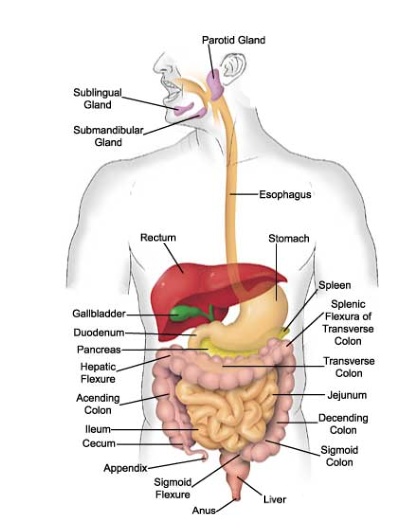

Food is passed down the gullet (oesophagus) into the stomach on being eaten. Cells in the lining of the stomach make acid and other chemicals which help to digest food. Stomach cells also make a thick liquid (mucus) which protects them from damage caused by the acid. The cells on the inside lining of the oesophagus are different and have little protection from acid.

There is a circular band of muscle (a sphincter) at the junction between the oesophagus and stomach. This relaxes to allow food down, but normally tightens up and stops food and acid leaking back up (refluxing) into the oesophagus. Therefore, the sphincter acts like a valve

Understanding Barrett’s oesophagus

Understanding Barrett’s oesophagus

Barrett’s oesophagus is a condition which affects the lower oesophagus. It takes its named after the doctor who first described it.

In Barrett’s oesophagus, the cells that line the affected area of gullet (oesophagus) become changed.

The cells of the inner lining (epithelium) of a normal oesophagus are pinkish-white, flat cells (squamous cells). The cells of the inner lining of the area affected by Barrett’s oesophagus are tall, red cells (columnar cells). The columnar cells are similar to the cells that line the stomach.

Another name sometimes used by doctors for Barrett’s oesophagus is columnar-lined oesophagus (CLO).

Risk caused by Barrett’s oesophagus

Though the changed cells of Barrett’s oesophagus are not cancerous. They have an increased risk, compared with normal gullet (oesophageal) cells, of turning cancerous in time. The changed cells in Barrett’s oesophagus can develop something called dysplasia. Though it is not cancerous, it is more likely than other cells to develop into cancer. It is often called a precancerous cell.

There are various levels of dysplasia, ranging from low-grade dysplasia to high-grade (severe) dysplasia.

Cells that are classed as high-grade dysplasia have a high risk of turning cancerous at some point in the future.

It is important to note that if one has Barrett’s oesophagus, the chance that it will progress to dysplasia, then to high-grade dysplasia, and then to cancer, is small. In the majority of cases, the changes in the cells remain constant, and do not progress. Studies have shown that, for a person diagnosed with Barrett’s oesophagus, their lifetime risk of developing cancer of the oesophagus is about 1 in 20 for men and about 1 in 33 for women.

Causes & Prevalence of Barrett’s oesophagus

The cause in most cases is thought to be long-term reflux of acid into the gullet (oesophagus) from the stomach. The acid irritates the lining of the lower oesophagus and causes inflammation (oesophagitis). With persistent reflux, eventually the lining (epithelial) cells change to those described above.

About 1 in 20 people who have recurring acid reflux have the probability of eventually developing Barrett’s oesophagus. The risk is mainly in people who have had severe acid reflux for many years. However, some people who have had fairly mild symptoms of reflux for years however can develop Barrett’s oesophagus.

Barrett’s oesophagus seems to be more common in men than in women. It typically affects people between the ages of 50 and 70 years. Other risk factors for Barrett’s oesophagus that have been suggested include smoking and being overweight, particularly if one carries excess weight around one’s middle.

Signs of acid reflux and oesophagitis

Heartburn which is a burning feeling rising from the upper tummy (abdomen) or lower chest up towards the neck is the main symptom. It is confusing, as it has nothing to do with the heart. Other common symptoms include:

- Belching

- A burning pain when one swallows hot drinks

- An acid taste in the mouth

- Bloating

- Feeling sick (nauseated).

- Pain in the upper abdomen and chest.

Like heartburn, these symptoms tend to come and go, and tend to be worse after a meal. People with Barrett’s oesophagus will usually have (or will have had in the past) the symptoms associated with acid reflux and inflammation of the gullet (oesophagitis).

Causes and effects of acid reflux

The circular band of muscle at the bottom of the oesophagus (the sphincter) normally prevents acid reflux. Problems occur if the sphincter does not work very well. This is common, but in most cases it is not known why it does not work so well. However, having a hiatus hernia makes one more prone to reflux. A hiatus hernia occurs when part of one’s stomach protrudes through the lower chest muscle (diaphragm) into the lower chest.

Most people have heartburn at some time, perhaps after a large meal. However, about 1 in 3 adults have some heartburn every few days, and nearly 1 in 10 adults have heartburn at least once a day. In many cases it is mild and soon passes. However, it is quite common for symptoms to be frequent or severe enough to affect quality of life. It is people who have severe and long-standing reflux who are more likely to develop Barrett’s oesophagus.

Healing acid reflux

A medicine which prevents one’s stomach from making acid is a common treatment and usually works well. Some people take short courses of treatment when symptoms flare up. Some people need long-term daily treatment to keep symptoms away. An operation to tighten the sphincter muscle is an option in severe cases which do not respond to medication, or where full-dose medication is needed every day to control symptoms.

There are also various things that one can try to change in one’s lifestyle that may help to treat acid reflux. Ex Losing weight if one is over weight, Stopping smoking, reducing alcohol intake.

Detection of Barrett’s oesophagus

Barrett’s oesophagus itself usually causes no symptoms. However, one is likely to have, or have had, the symptoms of long-standing or severe reflux disease described earlier. The general investigations that can be done are-

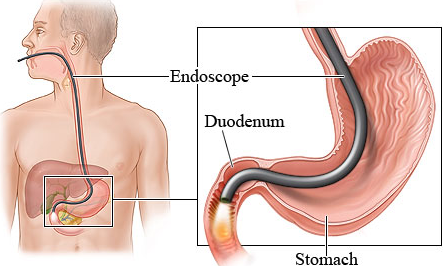

Gastroscopy (endoscopy)

You may have a gastroscopy if you have severe or persistent symptoms of acid reflux. For this test, a thin, flexible telescope is passed down the gullet (oesophagus) into the stomach. This allows a doctor or nurse to look inside. This test can usually help to diagnose Barrett’s oesophagus. The change in colour of the lining of the lower oesophagus from its normal pale white to a red colour strongly suggests that Barrett’s oesophagus has developed.

A biopsy

A biopsy

If Barrett’s oesophagus is suspected during gastroscopy then several small samples (Biopsy) are taken of the lining of the oesophagus during the gastroscopy. These are sent to the laboratory to be looked at under the microscope. The characteristic columnar cells which are described above confirm the diagnosis. The cells are also examined to see if they have any signs of dysplasia.

Treating Barrett’s oesophagus

Curing of acid reflux

This treatment is as described above. You are likely to be advised to take acid-suppressing medication for the rest of your life. It is unclear as to whether treating the acid reflux helps to treat or reverse your Barrett’s oesophagus and more studies are ongoing. However, this treatment should help any symptoms that you may have.

Surveillance (Monitoring)

When one has been diagnosed with Barrett’s oesophagus, one may be advised to have a gastroscopy and biopsy at regular intervals to monitor the condition. This is called surveillance. The biopsy samples aim to detect whether dysplasia has developed in the cells, in particular if high-grade dysplasia has developed.

The exact time period between each gastroscopy and biopsy sample can vary from person to person. It may be every 2-3 years if there are no dysplasia cells detected. Once dysplasia cells are found, the check may be advised every 3-6 months or so. If high-grade dysplasia develops, you may be offered treatment to remove the affected cells from the gullet (oesophagus).

There are however varied opinions as to the value of surveillance and, if it is done, how often it should be done. Briefly, some doctors argue that most people with Barrett’s oesophagus do not develop cancer. Many people would need to have regular gastroscopies to detect the very few who develop high-grade dysplasia.

In addition, complications are likely to occur in a small number of people who have gastroscopy. And, even if one develops high-grade dysplasia and has treatment, there is a risk of developing complications from treatment.

The traditional way- Operation

If you develop high-grade dysplasia or cancer of the oesophagus, the traditional treatment is to have an operation to remove the oesophagus (oesophagectomy). This is a major operation and complications following surgery, sometimes serious and life-threatening, are not uncommon. However most people who develop Barrett’s oesophagus do not go on to need an oesophagectomy. Also, newer therapies that have recently been developed are becoming more popular options if one develops high-grade dysplasia or early cancer.

Latest treatments

Various ways of removing just the abnormal dysplastic cells from the lining of the oesophagus (or even early cancers that just affect the lining on the oesophagus) have recently been developed. These include the following:

- Argon plasma coagulation. This treatment uses a jet of argon gas, together with an electric current, to burn away dysplastic cells.

- Epithelial radiofrequency ablation (EFA). This treatment uses a radiofrequency energy coil. Again, this involves a gastroscopy. During the procedure a small coil is guided towards the abnormal section of your oesophagus. The coil then emits heat energy which destroys the abnormal cells. Nearby normal cells then multiply and replace the destroyed abnormal cells.

- Endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR). This is a procedure that is done via instruments passed down the side of an gastroscope. Basically, the affected inner lining of the oesophagus is stripped off.

- Photodynamic therapy (PDT). This is a type of laser treatment. It has been used in the past but has been largely replaced by radiofrequency ablation.

CONCLUSION

Abnormality of the cells that line the lower gullet (oesophagus) is termed as Barret’s oesophagus. The main cause is long-standing reflux of acid from the stomach into the oesophagus. Such people bear an increased risk of developing cancer of the oesophagus. Though the chances of risk are slim, one may be advised to have regular endoscopies to detect precancerous changes to the cells in the oesophagus. Treatment to remove or destroy the precancerous cells may be advised in case precancerous changes develop.